Shocked (a new musical)

“Brave and exciting” –Tony Award-winning director

Story by David Michael Slater and Ernest Ebell

Libretto by David Michael Slater

Music and lyrics by Ernest Ebell

In development – samples available

SHOCKED is a new bio-musical about psychologist Stanley Milgram, who shocked the world by proving how easily ordinary people will commit extraordinary harm.

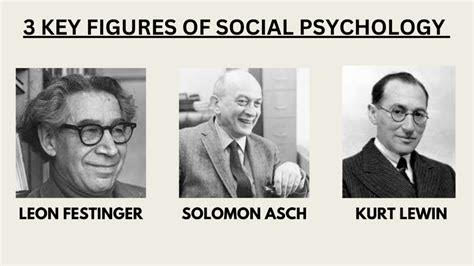

Obedience to Authority: How do people behave under authoritarian regimes, and what, if anything, can be done to resist them? It’s an important question for our time, and it was an important question for famed social psychologist Stanley Milgram in the 1960s when the world was still grappling with the aftermath of World War II.

Obedience to Authority: How do people behave under authoritarian regimes, and what, if anything, can be done to resist them? It’s an important question for our time, and it was an important question for famed social psychologist Stanley Milgram in the 1960s when the world was still grappling with the aftermath of World War II.

Shocked tells the true story of Milgram, who sought to learn how the Holocaust happened. In his most famous experiments, he explored what people will do when instructed by an authority figure to deliver increasingly powerful shocks to a stranger. He wanted to know how many would comply and how far they would go. What he discovered shocked the world, but what he learned might save it.

Shocked was conceived in the wake of the Tree of Life Synagogue massacre, a wakeup call that, for all the progress society has made over the past eighty years, antisemitism still runs deep. And while this story is focused on the specifics of Milgram grappling with antisemitism, the themes speak to the plight of all marginalized communities suffering under authoritarian regimes.

Shocked was conceived in the wake of the Tree of Life Synagogue massacre, a wakeup call that, for all the progress society has made over the past eighty years, antisemitism still runs deep. And while this story is focused on the specifics of Milgram grappling with antisemitism, the themes speak to the plight of all marginalized communities suffering under authoritarian regimes.

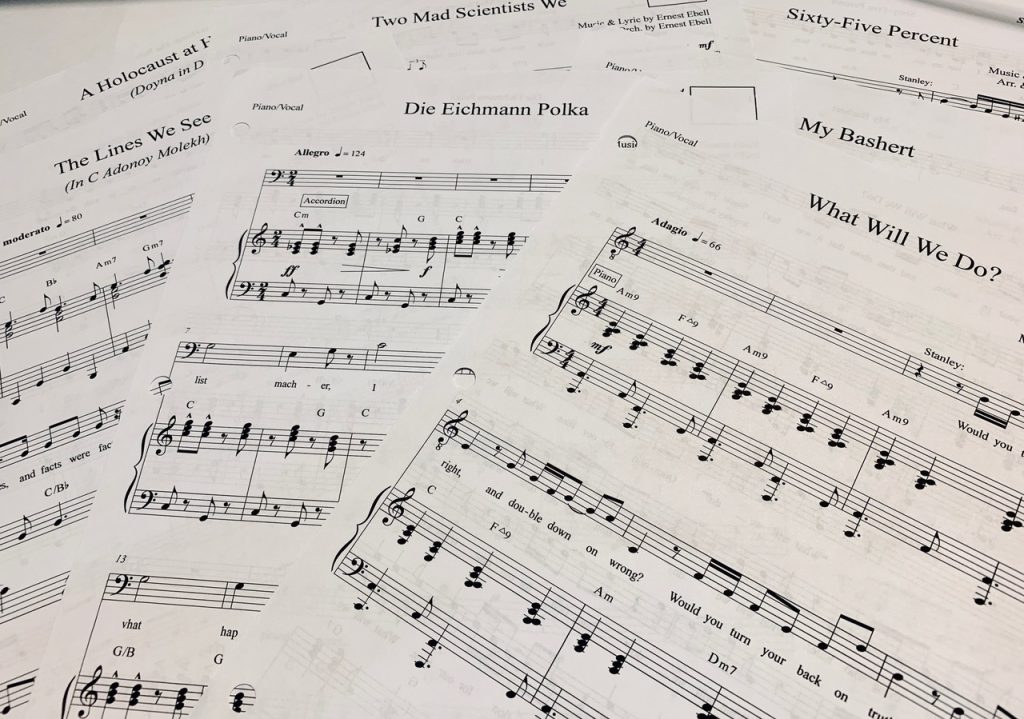

Read Slater reaction piece for the AP: First Person: A mass murder in Mr. Rogers’ neighborhood

Written for an Off-Broadway or Regional Theater venue, the book of the show, cleverly constructed in rhymed verse by David Michael Slater, will have audiences laughing through their tears. The score, by Ernest Ebell, is wonderfully complex and utilizes styles ranging from Klezmer to Bebop, Minuet to Musical Comedy, each deployed to best illuminate characters and situations. Shocked is written for an Off-Broadway scale venue, with a cast of 10 (utilizing several actors in multiple roles), and an orchestra of 6. Piano/Vocal parts and some full scores available upon request.

(Think Fiddler meets Cabaret

Synopsis

Act I

In a prologue, Sasha Milgram is being interviewed about her late husband, Stanley. She explains that as a famous social psychologist, he stood on the shoulders of giants (“Intro to Psychology”), and that fundamentally, he was asking why people do what they do (“Social Psychology 101”). The story of her husband then begins, as Sasha takes us back in time to The Bronx, New York, where, despite the day’s news of the surrender of Nazi Germany, young Stanley Milgram is warned by Mrs. Shrekn, his teacher at Hebrew School, that a Holocaust can happen anywhere, even in America (“A Holocaust at Home”). Later, Stanley’s parents’ efforts to reassure him that he is safe here (“The Melting Pot”) are defused by the arrival of relatives from Europe who have, in fact, survived the Holocaust. [Throughout the rest of the play, ethereal Survivors will be watching Stanley]. A year later, at his Bar Mitzvah, Stanley commits himself to understanding what has happened to his people (“Bar Mitzvah Song”) and (“The Hell We Ever Do to You?”). Eight years later, Stanley is an undergraduate, and in a conversation with his high school friend, Philip Zimbardo, the two decide to pursue graduate studies in Social Psychology (“Two Mad Scientists We”).

Stanley is accepted at Harvard, where he becomes an assistant to Solomon Asch, whose famous Line Experiment showed that one-third of subjects would deliberately give wrong answers, or even alter their reality, just to fit in with a group. This prompts Stanley to ask how this can happen, so that he can “fix” the problem (“The Lines We See”).

After receiving his PhD. (“Milgram Minuet I in A plus student”), Stanley accepts a position at Yale, and upon seeing the news that Adolph Eichmann has been captured and will be put on trial in Israel (“Die Eichmann Polka”), he creates his most famous and controversial work, the Obedience to Authority Experiment. Shortly after his project is approved by Yale (“Milgram Minuet II in G, That’s Interesting”), Stanley meets Sasha (a dancer, working on a degree to become a social worker), and they fall in love (“My Bashert“).

After receiving his PhD. (“Milgram Minuet I in A plus student”), Stanley accepts a position at Yale, and upon seeing the news that Adolph Eichmann has been captured and will be put on trial in Israel (“Die Eichmann Polka”), he creates his most famous and controversial work, the Obedience to Authority Experiment. Shortly after his project is approved by Yale (“Milgram Minuet II in G, That’s Interesting”), Stanley meets Sasha (a dancer, working on a degree to become a social worker), and they fall in love (“My Bashert“).

The experiments begin, and Stanley is bitterly disappointed to find that 65% of his subjects (“Sixty-Five Percent”) are willing to administer potentially dangerous electrical shocks to another person, simply because they were told to do so by an authority figure.

Act II

Stanley continues his experiments on Obedience to Authority, discussing the ethics (“Ethics- Schmethics!”) of his work with his now-fiancé Sasha, and the validity of his results with Zimbardo (“American Eichmanns”). Growing more and more agitated by his results, he is confronted by the ghost of Mrs. Shrekn, asking him (“How Else Should It Go?”), as he completes his work. Stanley accepts a position at Harvard, but with the publication of his experiments and mainstream media attention to them, he becomes one of the most polarizing figures in Social Psychology. Meanwhile, after reading news of the Kitty Genovese murder, Sasha has a dream in which she is Kitty, with bystanders watching the murder, but doing nothing about it (“The Kitty Genovese Ballet”).

Stanley creates a new experiment, showing us just how connected we are to one another (“Six Degrees of Separation”), but despite this latest triumph, he is denied tenure at Harvard (“Milgram Minuet III in B flatly denied”), due to the controversial nature of his earlier work. A few years pass, and Philip Zimbardo, now in California, has created the Stanford Prison Experiment, and as a result, he has become, like his friend Stanley, infamous for his work (“Ain’t Psychology Grand?”).

Stanley has moved on to City University of New York, where exhaustion, amphetamines, continued upset over his rejection at Harvard, ongoing criticisms of his work, and pressure to finish writing his book have combined to give him a near mental breakdown. It is Sasha who gets him through it (“Two Good People”). His book, Obedience to Authority, is published, and Stanley becomes exponentially more famous, but it does not lay the criticisms of his work to rest. A decade passes, and in 1984, he is often asked to give lectures about his work as it might relate to George Orwell’s 1984. In a classroom lecture, he is sharing his insights on how we might resist obedience to malevolent authorities when he is struck down by a heart attack.

In the epilogue, we are brought back to Sasha’s interview, in which she talks about her husband’s untimely death and explains that as a social worker, she is currently working with Holocaust survivors. Given what we have learned from Stanley’s work, the full company asks us, finally, (“What Will We Do?”).